70 Years of Liberation, 30 Years into the Future

The Road to Reconciliation and

Cooperation

Uncovering the historical truth is key to the peace and prosperity of Northeast Asia.

I Am Not a Comfort Woman.

Over 2 decades have passed since the late Kim Hak-sun became the first person in the world to testify as a victim of the Japanese Imperial ArmyвҖҷs вҖңcomfort womenвҖқ sexual slavery on August 14, 1991. Since then, a rally has been held every week on Wednesdays in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul by the former вҖңcomfort womenвҖқ victims to demand an apology from the Japanese government. It has since become the world's oldest rally with a single theme. However, the Abe government not only continues its refusal to accept responsibility for its wartime atrocities, but is also taking steps to turn Japan into a nation capable of waging another war.

Celebrating the 70th Independence Day, KBS World Radio aims to share the views of director Cho Jung-rae, who is currently working on a film on вҖңcomfort womenвҖқ titled Gwi-hyang (SpiritsвҖҷ Homecoming) and actress Seo Mi-ji, who indirectly experienced the pain of the вҖңcomfort womenвҖқ victims through her role in the movie. Through the vivid testimonies of the victims and the efforts of civic groups and experts in and outside of the country, we wish to inform Japan that future partnership and peace in Northeast Asia will only be possible when it faces its past.

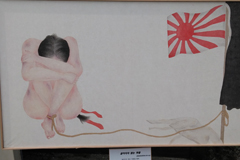

Kang Il-chul, the "comfort woman" victim painted "Girls Being Burned", which became the inspiration for the film "Spirits" HomecomingвҖқ

"Comfort woman" victim Kim Bok-dong

"Comfort woman" victim Lee Yong-soo, and actress Seo Mi-ji of the film "SpiritsвҖҷ Homecoming"

Statue of Kim Hak-sun, the first "comfort woman" victim to reveal herself to the public as a victim

House of Sharing, site of the gravestones of the "comfort women" victims.

Paintings depicting "comfort women" victims

"Comfort women" victim halmonis (grandmothers) enjoying an event at the House of Sharing

Nagahama Kazue, volunteer at the House of Sharing

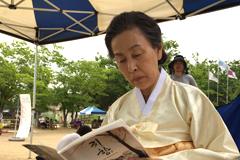

Yun Jung-ok is a former Ewha WomanвҖҷs University professor and the first to raise public awareness of the "comfort women" victims.

Filming of a shamanistic ritual (gut) in the last scene of the film "SpiritsвҖҷ Homecoming"

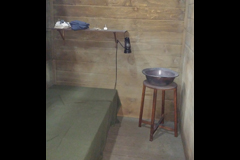

"Comfort station" film set for the film "SpiritsвҖҷ Homecoming"

"Comfort station" film set for the film "SpiritsвҖҷ Homecoming"

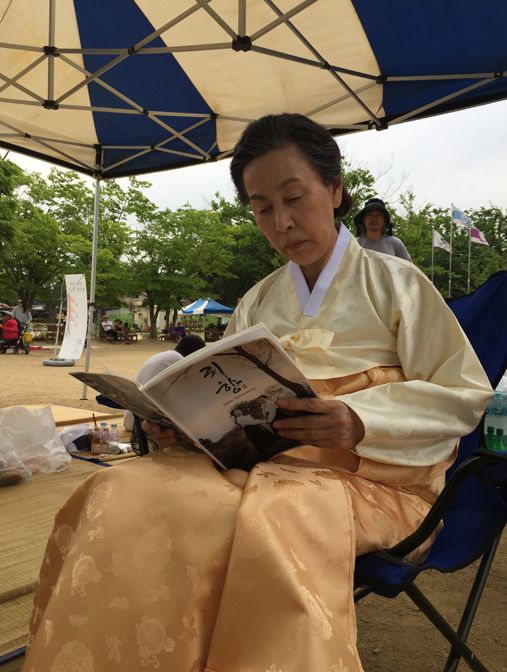

Sohn Sook, lead actress of "SpiritsвҖҷ Homecoming"

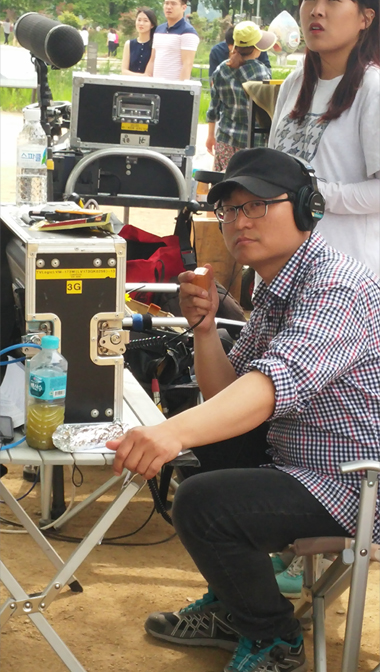

Cho Jung-rae, director of "SpiritsвҖҷ Homecoming"

Seo Mi-ji, actress who plays Young-hee in "SpiritsвҖҷ Homecoming"

Banner at the after party of the film "SpiritsвҖҷ Homecoming"

Special Program Marking the 70th Anniversary of KoreaвҖҷs Liberation from Japanese Colonial Rule: IвҖҷm not a вҖҳComfort Woman.вҖҷ

Part 1: SpiritsвҖҷ Homecoming

N: A man is singing a folk song, walking along the ridges between rice paddies. He is carrying his 14-year-old daughter, Jung-min, on an A-frame carrier on his back. The image of the happy father and daughter is beautiful.

The scene is from a movie titled вҖңSpiritsвҖҷ Homecoming,вҖқ which describes the plight of Korean sex slaves for Japanese troops during World War II. This scene was filmed at the Seodeok field in Geochang, South Gyeongsang Province. According to the filmвҖҷs director, Cho Jung-rae, it is an old, peaceful rural area where a full 360-degree rotation of the camera shows a vast, serene field. Here, Jung-min had a happy childhood.

N: As did the elderly victims of JapanвҖҷs wartime sexual slavery. Kang Il-chul was the youngest in a family of 12 children, and she was the darling of the family.

My hometown is Sangju, North Gyeongsang Province. My family ran a business of dried persimmons. As I was the youngest child in the family, my parents adored me and my sisters would give me a piggyback ride. I would cry if I wasnвҖҷt allowed to embrace my momвҖҷs bosom.

N: Lee Yong-soo cared for her younger twin brothers as if she was their mother. The cheerful girl could sing very well.

I liked to play cute tricks, and I could sing and dance well. People around me said they wouldnвҖҷt have any fun without me. I raised the twins, often carrying them on my back. They would look for their older sister, not their mom.

N: Kim Bok-dong, a young girl full of dreams, enjoyed playing hide-and-seek and hopscotch with her friends.

I hung out with friends all the time and we used to gather round in the village to play hopscotch and other things. Peaceful days passed, and there was nothing to worry about. I wasnвҖҷt lonely as I had younger siblings. I thought all I had to do was study hard.

N: However, from the moment when they were forced to serve as sex slaves, the lives of these young girls turned into a nightmare. 70 years have passed since Korea was liberated from Japanese colonial rule, and those girls have now become old women. But they are still living in miserable pain to this day.

Even though our nation was liberated decades ago, we havenвҖҷt been liberated yet. I wouldnвҖҷt say weвҖҷre living a decent life.

N: The term вҖңcomfort womenвҖқ is a euphemism for women who were forced to provide sex to soldiers at the so-called вҖңcomfort stationsвҖқ operated by the Japanese army during World War II. Those girls who lived through unbelievably brutal times were called comfort women. But in reality, they were KoreaвҖҷs daughters who had their own names.

How am I a comfort woman? Why should I use the dirty name, вҖңcomfort womanвҖқ? IвҖҷm not a comfort woman. IвҖҷm Lee Yong-soo. This is the very name given by my mother and father.

Hello, everyone. Welcome to our special program on KBS World Radio. Marking the 70th anniversary of KoreaвҖҷs liberation from Japanese colonial rule, weвҖҷve prepared a two-part special program, вҖңIвҖҷm not a Comfort Woman.вҖқ This is part one titled вҖңSpiritsвҖҷ Homecoming.вҖқ Today, weвҖҷll share with our listeners the painful and miserable lives of Korean victims of JapanвҖҷs wartime sexual slavery.

N: On a Sunday in July, film director Cho Chung-rae visited the House of Sharing after completing his filming work. It had been quite a while since he last visited the shelter for surviving former sex slaves in Gwangju, Gyeonggi Province. It is the place where the old ladies who provided a motive for the movie вҖңSpiritsвҖҷ HomecomingвҖқ are staying. Among them, 88-year-old Kang Il-chul was forcibly dragged to a comfort station in Changchun, Jilin Province of China, in 1943. She was only 16 years old. Through her, director Cho came to learn the horrible history of former sex slaves for the first time.

N: 13 years ago, Cho visited the House of Sharing with his friends, bringing a drum with him. They were the members of a traditional percussion music club. He had previously learned about sexual slavery during World War II in school, but he knew little about the harrowing moments the victims had actually undergone. At the shelter, Cho happened to see a shocking painting. It portrays young girls who are burned alive in a large pit. When he asked what the painting was about, the old lady Kang said that all the girls were burned to death and she was the only person who miraculously survived.

I had a high fever and lost hair due to typhoid. The Japanese troops were worried that the epidemic might infect the soldiers. It was a precarious situation and I was in great danger. I was crawling out of the incinerator, when a soldier of the Korean independence army took me with him, carrying me on his back. It was a miracle.

N: The director had thought that most victims of sexual slavery were living somewhere in Korea after returning home. He couldnвҖҷt believe that a lot of girls had actually been killed.

He was so shocked that he suffered from severe body aches for days. He even had a dream that the souls of the elderly victims returned to their hometowns. After that, he was determined to make a movie from this heartrending story.

N: Do you know how old the girls were when they were forcibly taken to Japanese military brothels? Here is Kim Bok-dong, who is 90 years old now.

I was 14 years old. They said I would be sent to a factory producing military uniforms. I soothed myself thinking I wouldnвҖҷt die in a factory. But as it turned out I was dragged to a frontline area, as a comfort woman. I was brought to a number of regions, such as Taiwan, Gwangdong in China, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Sumatra and Java of Indonesia, and Singapore. They treated me like a bag, putting me on top of luggage in trucks.

N: 13 years ago, Cho visited the House of Sharing with his friends, bringing a drum with him. They were the members of a traditional percussion music club. He had previously learned about sexual slavery during World War II in school, but he knew little about the harrowing moments the victims had actually undergone. At the shelter, Cho happened to see a shocking painting. It portrays young girls who are burned alive in a large pit. When he asked what the painting was about, the old lady Kang said that all the girls were burned to death and she was the only person who miraculously survived.

I had a high fever and lost hair due to typhoid. The Japanese troops were worried that the epidemic might infect the soldiers. It was a precarious situation and I was in great danger. I was crawling out of the incinerator, when a soldier of the Korean independence army took me with him, carrying me on his back. It was a miracle.

N: The director had thought that most victims of sexual slavery were living somewhere in Korea after returning home. He couldnвҖҷt believe that a lot of girls had actually been killed.

He was so shocked that he suffered from severe body aches for days. He even had a dream that the souls of the elderly victims returned to their hometowns. After that, he was determined to make a movie from this heartrending story.

N: Do you know how old the girls were when they were forcibly taken to Japanese military brothels? Here is Kim Bok-dong, who is 90 years old now.

I was 14 years old. They said I would be sent to a factory producing military uniforms. I soothed myself thinking I wouldnвҖҷt die in a factory. But as it turned out I was dragged to a frontline area, as a comfort woman. I was brought to a number of regions, such as Taiwan, Gwangdong in China, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Sumatra and Java of Indonesia, and Singapore. They treated me like a bag, putting me on top of luggage in trucks.

One night, a soldier and a girl came to my house. The girl signaled to me. I thought she was fooling around with me, so I ignored her and sat at a spinning wheel. The girl approached me. She put her arm around my shoulders and covered my mouth. The soldier then poked me in the back with something and walked me off by force. Still, I thought they were playing a trick on me. I had no idea of what was going on. I never knew.

N: Lee was forced on the train right away. She took the train for the first time in her life and started on a long journey.

Farewell to my parents? No. I was taken away in the middle of the night. How could I ever say goodbye to anyone in that situation?

N: Just like Lee, Kang Il-chul also had to leave home without even a moment to see her parents.

My Parents didnвҖҷt know what was happening. They were not at home when I was taken away. After returning from school, I ate something and sat on the floor by myself. My parents didnвҖҷt know.

N: JapanвҖҷs Shinzo Abe Administration claims there is no proof that the Japanese military or government forcibly conscripted women to work as sexual slaves. Yun Jung-ok, former professor at Ewha WomanвҖҷs University, has been studying the comfort women issue all her life. She is over 90 years old. She brings a book titled вҖңComfort WomenвҖқ from her study filled with books and research material related to this issue and begins reading a particular phrase in a furious tone.

The Japanese Kwantung Army wanted to mobilize 20-thousand Korean women for sexual enslavement. This is shown in page 99 of this book. See? It is clearly stated that the Kwantung Army asked the governor-general of Korea to send 8,000 Joseon women as sexual slaves in order to conscript 20-thousand comfort women and that the 8,000 women were sent to the northeastern region of China.

N: Written by Yoshimi Yoshiaki, a Japanese modern history professor at Chuo University in Tokyo, this book was based on the document about comfort women written by JapanвҖҷs War Ministry in 1938. The professor unveiled the document in 1993. This contributed greatly to eliciting the Kono Statement, in which the Tokyo government acknowledged the Japanese militaryвҖҷs involvement in recruiting comfort women by force for its troops.

Professor Yun still vividly remembers the moment when she was almost taken away as a comfort woman. It was in spring of 1943, when she was a freshman at Ewha College.

A man wearing the Japanese military uniform brought a person who looked like an assistant. He handed out blue printed materials and told us to sign the papers with both thumbprints. We were so frightened that we felt we should follow his order. A similarly intimidating atmosphere prevailed in Korea at the time. Everything was done quickly. They distributed the papers and stamp pads. As soon as we signed the papers with our thumbprints, the papers were collected one by one from the back, just like test papers.

N: The girls were hauled into trucks, ships and trains. Yu Hee-nam recalls the moment.

They covered our heads with something black. When we boarded the ship, the windows of the cabins were all covered with something black so that light would not escape through the windows.

N: They finally arrived at unknown military units. There, something that the teenage girls could hardly endure began to happen.

N: The girls were placed on exam tables under the pretext of sanitary inspections. They were then sexually violated. The late Kim Hak-sun wailed when she recalled the humiliating and dreadful moment. She gave a public testimony in 1991 and became the first comfort woman to come forward.

I was only 17. I just turned 17 when a Japanese soldier brutally dragged me and raped me. It was no use crying. I tried to storm out of the room, but the dirtbag, the Japanese man, the soldier grabbed me and never let go of me. While being raped, I couldnвҖҷt stop crying. The experience was too heartbreaking for words.

N: Lee Yong-soo was even tortured with electric shocks because she resisted. Even today, she canвҖҷt look at her scars from the torture without shuddering.

It was just so horrible that I canвҖҷt even think about it. I suffered electric torture because I refused to enter the soldiersвҖҷ room. I still hear a strange sound. IвҖҷm not sure whether it comes from my head or my ears. I also have a scar on my belly. Why should I enter the soldiersвҖҷ room?

N: Aso Tetsuo was an army doctor who examined sexually transmitted diseases at comfort stations at the time. He wrote in his diary, вҖңWomen brought from Joseon were the best imperial gift granted by the emperor to Japanese soldiers.вҖқ The expression indicates that the Korean victims of sexual slavery were young women who had no sexual experience at all. Similar expressions are also found in the same diary. LetвҖҷs hear from Yoon Mi-hyang, president of the Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan.

It is also written that the women are a sanitary public toilet where Japanese soldiers can discharge their sexual desire. The sentence has conflicting concepts. The word вҖңsanitaryвҖқ suggests that the young, clean women were actually virgins. But the word вҖңtoiletвҖқ implies that these women were treated as a mere toilet to receive the soldiersвҖҷ sexual waste.

N: The Japanese military strictly managed comfort stations, even setting a guideline for the proportion of Japanese soldiers to sex slaves. Professor Su Zhiliang from the Comfort Women Research Center at Shanghai Normal University cites a comfort station in Nanjing as an example.

WeвҖҷve found a record about a comfort station in Nanjing. In the document, it is written that the proportion of Japanese soldiers to sex slaves is 178 to 1.

N: Kim Bok-dongвҖҷs testimony also backs this up.

On Saturdays, the soldiers would line up from 12 p.m. to 5 p.m. On Sundays, from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. When it was over in the evening, I could hardly stand up. My limbs got badly swollen. Medics then gave me medicines and shots so I would recover during the coming week before the same routine was repeated.

N: President Yoon Mi-hyang says that sexual slavery during World War II was an unprecedented war crime in human history.

The Japanese government planned the scheme as a policy, and the Japanese military recruited women and positioned them at the battlefields. In doing so, Japanese troops were provided with safe rape camps, namely, comfort stations, where they were allowed to rape women. The military examined and managed the venereal diseases of the women, who were robbed of their freedom and ended up serving Japanese soldiers as sex slaves. This can be defined as a war crime that had never existed before and will never occur again in human history.

N: Many of the girls who were dragged by the Japanese military were underage, and they hadnвҖҷt even had their first period. The same was true for Jung-min, the heroine of the movie вҖңSpritsвҖҷ Homecoming.вҖқ Actress Oh Ji-hye talks about one of the most distressing scenes in the movie.

The drafted girls include those who havenвҖҷt even had their first menstrual period. In a more heartbreaking scene, the heroine has her first period, while being raped. She falls asleep on the bed and has a dream. She wakes up, but she still canвҖҷt tell if she is awake or dreaming.

N: While playing the role of Jung-minвҖҷs mother who made cloth sanitary pads for her daughter, actress Oh felt a deep pang of sorrow.

The mother is making cloth sanitary pads called gaejim. While sewing the pads, the mother says, вҖңOh, my girl has grown up so fast. Congratulations, darling. YouвҖҷre now an adult.вҖқ The daughter keeps calling out for her mother. вҖңMom, mom...вҖқ Suddenly she wakes up. She soon realizes everything was a dream. How sad! She probably finds herself hoping to die. My heart ached with sympathy for the poor kid.

N: If the girls grew up normally, entering adulthood would have been something to celebrate. But in reality, these girls had to shed tears on the hard, cold beds at comfort stations, missing their mothers.

N: At comfort stations, girls were humiliated and sexually assaulted before dying.

According to Director Cho Jeong-rae, it felt like the temperature was exceptionally low at the movie set of a comfort station. It was in late April and warm spring was felt outside. Inside the set, however, people felt cold even if they were pulling on their winter parkas. They felt as though the souls of the ill-fated girls were there. It is said that actresses had dreams of the girls when they filmed the scenes of the comfort station. It was indeed a difficult experience, as they were terrified and felt guilty at the same time. Two actresses, Hong Se-na and Park Jae-won, share their feelings.

Hong: The director and us actresses, describe the scene of the comfort station as a scene from hell. I was really scared. Tears were suddenly welling up in my eyes.

Park: I cried a lot. I felt immensely sorry for the poor girls, and I cried so much.

N: Director Cho says he always made a bow before and after filming the scenes of the comfort station. The ritual reflected his hope that the souls of the girls would allow him to lay bare the truth and spread it widely.

N: The Pacific War was drawing near to an end. As the war was not going in JapanвҖҷs favor, the Japanese military began to eliminate all evidence of its comfort stations overseas.

N: Comfort stations and relevant documents were burned. Many of the girls were killed as well. In the movie, Jung-min and her friend Young-hee have a narrow escape. Unfortunately, Jung-min is shot while running away. She dies in Young-heeвҖҷs arms.

N: How many girls were killed and thrown aside out there?

Young-hee had to leave Jung-min, who died in her arms.

Back then, how many girls had to leave their dead friends behind and move on?

N: Imperial Japan lost the war, and Kim Bok-dong barely escaped death. Thinking about her stolen youth, she feels resentful and angry.

Eight long yearsвҖҰ. Back then, I even lost track of the time. After the war was over, I was detained at the U.S. militaryвҖҷs internment camp in Singapore. They found out the women there, including me, were Koreans. So, we were told to wait for a ship to come. The ship for refugees finally came and some 3,000 people boarded it. Only then did I realize that I was already 22 years old.

N: With other victims, Yu Hee-nam also got on the ship bound for Korea. But she couldnвҖҷt bring herself to return home.

Of course I had my family back home. But I couldnвҖҷt return. I was deeply ashamed. We, women, have traditionally had many things to cherish. I just lived, wandering from place to place. Who could ever say such a shameful thing? I was too embarrassed to go back home.

N: Some girls chose to take their own lives, with their hometowns only a short distance away, as they found it utterly disgraceful to return home with their soiled body.

Needless to say, the women desperately wanted to go home. But having gone through the awful experience, they were too ashamed to face their family. Also, they thought they would put their family to disgrace. For these reasons, many of them chose not to return home.

I will tell you a story. On the refugee ship, a girl heard someone shouting, вҖңWeвҖҷre almost there! I see Korean mountains over there.вҖқ The girl came out to the deck and saw her hometown, Busan, from a distance. But her joy didnвҖҷt last long. She murmured how she could see her parents with her dirty body. With these words, she jumped into the sea from the deck.

N: They returned home, home to a place they had missed so much even in their dreams. However, the hometowns they had cherished in childhood were gone. Lee Yong-soo recalls that only her twin brothers, who she used to carry on her back, remained alive.

I learned that my younger siblings and my parents had all died. Only my twin brothers were alive.

N: Kim Bok-dongвҖҷs mother was able to see her beloved daughter again for the first time in eight years. At first, she wouldnвҖҷt believe what her daughter said. She just couldnвҖҷt understand how on earth that kind of thing could happen.

My parents told me to get married, but that was simply impossible. When I told my mom about my story, she said I was telling a lie. She wouldnвҖҷt believe me. She said there was no place like that in the entire world. She scolded me for saying silly things because I didnвҖҷt want to get married. When she saw my miserable body, she was dumbfounded. My mother lamented bitterly, thinking she could not face her ancestors after death as she failed to manage her child properly. She couldnвҖҷt tell anyone, and she began to suffer from anger and depression.

N: Kim felt guilty about returning alive alone.

She was too often haunted by her appalling life at comfort stations. Every night, Kim was oppressed by a nightmare.

The girls who had been sent to the frontlines were all dead, except me. After I returned home, my mom gave me all sorts of medicines for one year to cure me. I was often startled while asleep. When I woke up, I wondered for a moment how and why I was there. Even if I stayed and slept in my own house, I felt as if it had been a strange place. For me, it was a near miracle just to stay alive.

They are totally unaware of the suffering victims. Japan claims that such women never existed. It is simply too ridiculous for words. I wish I could vent my anger, even with words, even just once, before I die.

N: The elderly victims had been afraid of going out into the world. But they were able to take courage after Kim Hak-sun testified in 1991 that she was in fact a former comfort woman. She was the first comfort woman ever to go public with her story.

Living all alone, I used to spend time watching TV in the evening. One day, I happened to see people on TV saying they have no idea what comfort women are. A Japanese person even said there were no such women at all and it was Korean people who traded women. I was so heartbroken. Actually, I had always been thinking of speaking out on this matter some day. Upon hearing the absurd claims, I was struck dumb and I cried hard. It was extremely frustrating that people were so unaware of what had actually happened to us. Moreover, Japan blatantly says that it never took any girls and things like that never happened, although there still are surviving witnesses like me. I burst into tears. I was shocked and stunned. ThatвҖҷs why I decided to start this.

N: Kim was 16 years old when she was taken by the Japanese troops. It was not until she was 67 that she spoke up, breaking a 51-year-long silence. KimвҖҷs testimony gave courage to other victims, who began to come forward. A reporting center for victims of JapanвҖҷs wartime sexual enslavement was set up on February 25, 1992. However, only 238 elderly women officially admitted that they were former comfort women. That was partly because many victims had already passed away. But for many others, it would be more painful to reveal their miserable past than to die. At first, Kim Bok-dong decided to pluck up courage and tell people the truth. But in reality, she could barely open her mouth.

I was tongue-tied at first. I had never stood up in front of people before, and moreover, I was truly ashamed to talk about my past. I didnвҖҷt think I could make it in my sober senses. So I grabbed a drink. As I was feeling a little tipsy, I was able to talk. But tears rushed to my eyes at the same time.

I wondered why I should say things like that.

N: Yu Hee-nam says that she should have died back then, if she had known she would be treated like this.

As a Korean woman, I should have killed myself then. From childhood, we had been taught that a woman would not be treated as a decent human being if she failed to serve only one husband all her life in this country of courteous people. Even if the husband might act like a fool, the wife was supposed to serve him faithfully until she dies in her husbandвҖҷs house. If the wife returns to her own parentвҖҷs house or remarries another man, she was not even regarded as a human. At that timeвҖҰ oh, I donвҖҷt want to say any moreвҖҰ It was just indescribableвҖҰ

N: After Kim Hak-sunвҖҷs testimony, other victims started to give similar testimonies one after another. Also, the Japanese governmentвҖҷs documents supporting their testimonies were disclosed.

In July 1992, then-Japanese Chief Cabinet Secretary Koichi Kato said in a statement that there was no coercion in the comfort womenвҖҷs mobilization, although the Japanese military was involved in it.

In August the following year, new Chief Cabinet Secretary Yohei Kono announced a statement, in which he acknowledged the forcible drafting of comfort women as sexual slaves to Japanese troops.

The Kono Statement said that the Japanese military was involved in the transfer of comfort women and the women were recruited against their will through coercion. But Japan still distorts the truth. The statement also said that the comfort women were mainly drafted by private recruiters in response to the request of the military. It sounds as if private recruiters had played the leading role in comfort womenвҖҷs mobilization. Citing this, Japanese government still does not recognize its legal responsibility.

N: Japan claims that it fulfilled its legal responsibility through the 1965 Korea-Japan Treaty. Here is Ahn Shin-gwon, director of the House of Sharing.

The Tokyo government claims that all issues regarding its colonial rule were settled in 1965. However, the 1965 Korea-Japan Basic Treaty deals with property rights of Korea under colonial rule. It does not include the right to demand compensation for victims of war crimes against humanity committed by the Japanese military.

N: International organizations have released a series of reports indicating that the Korea-Japan Treaty failed to reflect legal compensation for Korean victims of sexual slavery.

Reports by Radhika Coomaraswamy, a former U.N. special rapporteur on violence against women, and another former U.N. special rapporteur Gay McDougall noted that the 1965 Korea-Japan Treaty did not deal with the comfort women issue. In another report released by Amnesty International in 2005, it is stated that the 1965 treaty and other agreements of involved countries did not settle the comfort women issue. The report urged Japan to pay compensation to the victims.

N: However, Tokyo has erased the history of its sexual slavery of women during World War II in the textbooks, while extremists in Japan are calling the victims вҖңvoluntary prostitutes.вҖқ They are killing these girls twice.

N: Is the Japanese government simply waiting for all the elderly victims to die? A 72-year-old Japanese woman Kazuko Nagahama has been engaging in volunteer work at the House of Sharing for the last ten years. Her heart feels heavy when she sees the old ladies there, who are getting weaker and weaker.

Obviously, these women have become noticeably fragile. I can clearly see that. IвҖҷve seen five women here pass away in the last ten years. While pushing the elderly womenвҖҷs wheelchairs and looking at them from behind, I feel my heart is getting heavier.

N: ItвҖҷs uncertain how many more years the aging women can survive. Lee Yong-soo feels pressured, as she is also running out of time.

My mind is kind of urgent these days, as my elderly friends are dying one by one. I was so frustrated that I even said in the U.S. that I would live 200 years. I try hard not to get sick. I get up early in the morning, dying my hair or taking medicines. My life has been weary, filled with hardships and regrets.

N: On March 4, when a chilly wind was still blowing, the so-called вҖңWednesday RallyвҖқ was held in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul. The rally has been held every Wednesday since January 8, 1992. It was the 1,168th such gathering.

N: The demonstration has been recorded in the Guinness Book of World Records as the longest rally on a single issue. It is also a sign that the comfort women issue has remained unsettled for such a long time. The victims had never missed the rally thus far. It is difficult for these old, weak halmonis(н• лЁёлӢҲ) or grandmas to even walk. As soon as the rally begins, however, the light in their eyes changes and their voice rises higher.

N: The lines of the song say, вҖңLetвҖҷs live like a hard rock, undaunted by despair.вҖқ Kim and Lee are singing the song energetically. How can these 90-year-old women sing so powerfully?

I should win over Japan by all means before I die. Then, I can say something to other victims in heaven. If I fail to resolve this problem, and if they ask me what IвҖҷve done for all those years, I have nothing to say.

N: Lee says that she will live to be 200 years old so she can receive an official apology from Japan. Only then, she says she can die in peace and ease her guilty feeling about returning alive alone.

Sadly, numerous young girls met tragic, untimely deaths in foreign lands many years ago. Now, through his film, Director Cho hopes to take the spirits of the girls back home.

N: On a quiet summer afternoon in early June, the director shot the scene of a shamanistic ritual in front of a 400-year-old zelkova tree by a river in Yangsuri, east of Seoul. This scene is the highlight of the movie.

Veteran actress Son Sook performed the role of Young-hee, now an old woman who returned alive long ago. While filming the scene, Son said that she felt like she had finally paid her debt to the girls.

I think almost all women living in this age feel guilty for what the elderly victims had gone through. WeвҖҷre all indebted to them. But how can we pay the debt? For me, this was an opportunity to pay back, though only in a small way.

N: When the ritual for the spiritsвҖҷ homecoming starts, a strong wind suddenly begins blowing as if the souls were responding to the exorcistвҖҷs chant. At this scene, actress Hwang Ha-seong, who played the role of the exorcist, was so startled that she almost cried.

The wind was blowing so violently. It made my hair stand on end. I felt like I was possessed by a mysterious spirit. My body was trembling, and this gave me goose bumps. I was close to tears.

N: A group of butterflies are flying around the zelkova tree. The butterfly is often compared to a spirit. Having this in mind, the director expressed the spirits of the girls in butterfliesвҖ”butterflies of peace symbolizing the elderly victims.

N: In a peaceful rural village, Jung-min returns home after playing at the fields. She jumps on the floor and enjoys a meal with her parents. This is the last scene of the film.

Even if it is only in the film, Director Cho hopes to bring the spirits of the girls back home and offer them a spoonful of warm, newly-cooked rice, at least in his movie.

N: The past that we have not lived through only remains in record. But when we face people who still have a memory about the past, history begins to come alive and becomes a reality. So does the history of the elderly victims of JapanвҖҷs wartime sexual slavery.

In the mid-1990s, Japanese journalist Doi Toshikuni captured the lives and deaths of six such victims on film for about two years. Now, he shares his opinion about the essence of the comfort women issue.

There are women who suffered damage. As a result, their entire lives were destroyed. This is the essence of the comfort women issue. Every single one of them was deprived of their dignity that would otherwise enable them to lead decent lives. And they have been troubled by the painful memories for all those years.

There lived an old Korean woman near Dongying, southern China. She grabbed our hands and wept. Unfortunately, she couldnвҖҷt communicate with us because she forgot the Korean language. When we were with her, we sang Arirang. We gave it a try. Then, the woman, who couldnвҖҷt speak Korean, also began to sing ArirangвҖҰ Three of us all cried.

N: Imperial JapanвҖҷs wartime sexual slavery during World War II completely destroyed the lives of countless young girls. The comfort women issue indisputably comprises the disturbing history of mankind. WeвҖҷll keep our fingers crossed that the spirits of the girls who died in foreign lands will return home and rest in eternal peace.

N: That concludes вҖңSpiritsвҖҷ Homecoming,вҖқ the first part of our special program marking the 70th anniversary of KoreaвҖҷs liberation from Japanese colonial rule. Thank you for tuning in, and please join us again tomorrow for the second part of the program. Goodbye, everyone.

'Spirits Homecoming' Movie Trailer

'In 2015, the spirits of little girls wandering in strange lands return to their home.'